Regards croisés sur le paysage

Depuis quelques décennies, le concept de paysage connaît un regain d’intérêt, et donne lieu à de multiples approches : géographie, philosophie, urbanisme, histoire de l’art, architecture, études environnementales…. Il peut être compris comme un territoire habité et travaillé par les sociétés qui l’organisent ; comme l’environnement matériel et physique des sociétés ; comme une représentation artistique, culturelle et sociale. En ce sens, le paysage est simultanément, et paradoxalement, à la fois un objet de contemplation, et un objet constitué par les pratiques sociales, économiques et politiques d’acteurs agissant dans le monde. Le paysage permet ainsi une réflexion renouvelée sur notre rapport au monde et à la nature, particulièrement à l’ère de l’anthropocène, et permet ainsi de penser une nouvelle dimension du politique qui ne soit plus dans un rapport purement exploitatif à l’égard de la nature.

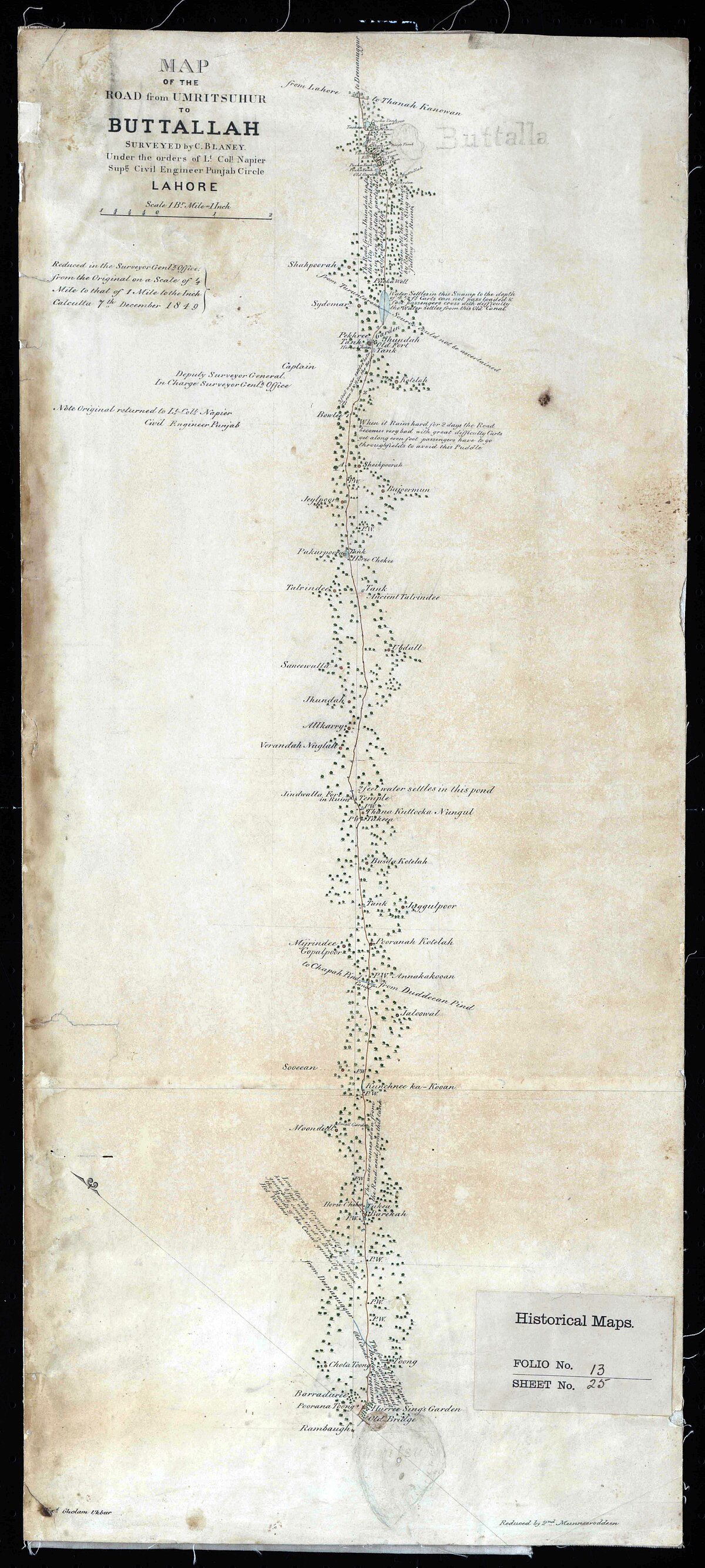

The construction of post-war Europe was not merely a political innovation; it was simultaneously a visual, spatial, and cultural experience – as well as a fundamentally open and generous project: it was about creating a common landscape, in every sense of the term. The concept of landscape, at the crossroads of geography, philosophy, art, architecture, history, politics, and environmental studies, appears an important nexus to explore the various dimensions of the European experiment. The EU, as an original political space, is vividly represented through its myriad spaces and landscapes.

The European Landscape Convention, adopted in 2000 and aimed at promoting the protection, management and planning of European landscapes, strongly emphasises how the landscape both embodies and fulfils the fundamental aims of the EU project itself: “The landscape contributes to the formation of local cultures and (…) is a basic component of the European natural and cultural heritage, contributing to human well-being and consolidation of the European identity” (Preamble). In other words, Europe and its union are made visible and manifest in large part in landscapes.

While landscape is often understood as a beautiful panoramic scenery, contemplated by a detached observer, it is also the environment as formed, shaped, lived, and experienced by a community, “a way to inhabit the land” (Dauphant, 2018). Landscapes are democracy in vivo, as people shape, form, use and benefit from the landscapes around them. In that sense, landscapes are a genuine res publica, and are as such increasingly understood in a broader social and political framework; they are seen to encompass substantive relationships between the human being and her environment. The link between landscape and well-being is now well established (Abel, Abraham, 2009; Coles, Millman, 2013), and this has been proven again during the pandemic; as has the relationship between landscape and democratic participation, with the emerging notion of landscape citizenship (Wall, Waterman, Wolf, 2021).

The notion of landscape has, crucially, helped renew the reflection on nature and ecology, and has become an important element in the reflection on the common good in the age of the Anthropocene. Numerous scholars have noted how the focus on landscape is key tool in re-thinking the relationship to nature, and the world in general: as a matter of fact, it is singularly suited to re-imagine politics away from a purely exploitative relationship to nature (Latour, 2018; Besse, 2018). Landscapes are part of our environmental aesthetics, but also of our environmental politics; in fact, ecology, and environmental issues more generally, can no longer be thought without the notion of landscape.

Our inter-disciplinary and multi-faceted project will explore how landscapes are and can be a site of aesthetic and cultural belonging, of political largesse, as well as embody European principles and values. The landscape provides a model for understanding togetherness and community, unity, diversity and inclusiveness, as well as a renewed relationship to the environment. As such, it is both a theoretical and a practical object, and the “Landscape” project will duly embody both dimensions.

European Landscapes – Module Jean Monnet

Jean Monnet Actions in the field of Higher Education Teaching and Research Erasmus+ programme (Erasmus)

Numéro de proposition : 101085544

Nom court : Landscape

Durée : 36 mois

Organisation participante : Université de Lille - Faculté des humanités

Etablissements partenaires : Europa-Universität Viadrina Frankfurt (Allemagne), Uniwersytet Wroclawski (Pologne), Centre of Philosophy University of Lisbon (Portugal) et Géographie-Cités UMR-8504 (France).